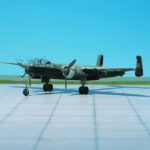

TYPE: Long-range fighter and fighter bomber

ACCOMMODATION: Pilot only

POWER PLANT: One Packard (Rolls Royce) V-1650-7 Merlin liquid-cooled engine, rated at 1,720 hp at WEP (War Emergency Power)

PERFORMANCE: 440 mph

COMMENT: The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang was an American long-range, single-seat fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II and other conflicts. The Mustang was designed in 1940 by North American Aviation (NAA) in response to a requirement of the British Purchasing Commission. The commission approached NAA to build Curtiss P-40 fighters under license for the Royal Air Force (RAF). Rather than build an old design from another company, NAA proposed the design and production of a more modern fighter. The prototype NA-73X airframe was completed on September 1940, 102 days after contract signing, achieving its first flight on October same year.

The Mustang was designed to use the Allison V-1710 engine without an export-sensitive turbosupercharger or a multi-stage supercharger, resulting in limited high-altitude performance. The aircraft was first flown operationally and very successfully by the RAF as a tactical-reconnaissance aircraft and fighter-bomber (Mustang Mk I). In mid 1942, a development project known as the Rolls-Royce Mustang X, replaced the Allison engine with a Rolls-Royce Merlin 65 two-stage inter-cooled supercharged engine. During testing, it was clear the engine dramatically improved the aircraft’s performance at altitudes above 15,000 ft without sacrificing range. Following receipt of the test results and after further flights by a number of USAAF pilots, the results were so positive that North American began work on converting several aircraft developing into the P-51B/C (Mustang Mk III) model, which became the first long range fighter to be able to compete with the Luftwaffe‘s fighters. The definitive version, the NAA P-51D Mustang, was powered by the Packard V-1650-7, a license-built version of the two-speed, two-stage-supercharged Merlin 66, and was armed with six .50 caliber AN/M2 Browning machine guns. Over twenty variants of the North American P-51 Mustang fighter were produced from 1940, when it first flew.

Following combat experience the P-51D series introduced a “teardrop”, or “bubble”, canopy to rectify problems with poor visibility to the rear of the aircraft. In the United States, new moulding techniques had been developed to form streamlined nose transparencies for bombers. North American designed a new streamlined plexiglass canopy for the P-51B which was later developed into the teardrop shaped bubble canopy. In late 1942, the tenth production P-51B-1-NA was removed from the assembly lines. From the windshield aft the fuselage was redesigned by cutting down the rear fuselage formers to the same height as those forward of the cockpit; the new shape faired in to the vertical tail unit. A new simpler style of windscreen, with an angled bullet-resistant windscreen mounted on two flat side pieces improved the forward view while the new canopy resulted in exceptional all-round visibility. Wind tunnel tests of a wooden model confirmed that the aerodynamics were sound. The new model Mustang also had a redesigned wing; alterations to the undercarriage up-locks and inner-door retracting mechanisms meant that there was an additional fillet added forward of each of the wheel bays, increasing the wing area and creating a distinctive “kink” at the wing root‘s leading edges.

Other alterations to the wings included new navigation lights, mounted on the wingtips, rather than the smaller lights above and below the wings of the earlier Mustangs, and retractable landing lights which were mounted at the back of the wheel wells; these replaced the lights which had been formerly mounted in the wing leading edges. The engine was the Packard V-1650-7, a license-built version of the Rolls-Royce Merlin 60 series, fitted with a two-stage, two-speed supercharger.

The P-51D became the most widely produced variant of the Mustang. The P-51D started arriving in Europe in mid-1944 and quickly became the primary USAAF fighter in the theater. It was produced in larger numbers than any other Mustang variant. Nevertheless, by the end of the war, roughly half of all operational Mustangs were still P-51B or P-51C models.

The aircraft shown here belonged to the 343rd FS, 55th, FG, 8th USAAF, stationed at Wormingford, Essex, United Kingdom, in September 1944 (Ref.: 24).