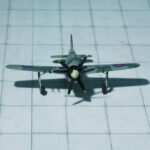

TYPE: Medium bomber, anti-shipping bomber

ACCOMMODATION: Crew of five

POWER PLANT: Two Rolls-Royce “Merlin” X liquid-cooled engines, rated at 1,145 hp each

PERFORMANCE: 230 mph at 16,500 ft

COMMENT: The Armstrong Whitworth Whitley was one of three British twin-engined, front line medium bomber types that were in service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) at the outbreak of the Second World War. Alongside the Vickers Wellington and the Handley Page Hampton, the Whitley was developed during the mid-1930s according to Air Ministry Specification B.3/34, which it was subsequently selected to meet. In 1937, the Whitley formally entered into RAF squadron service; it was the first of the three medium bombers to be introduced.

Following the outbreak of WW II in September 1939, the Whitley participated in the first RAF bombing raid upon German territory and remained an integral part of the early British bomber offensive. By 1943, it was being superseded as a bomber by the larger four-engined “havies” such as the Short Stirling, Handley Page Halifax and Avro Lancaster.

Its front line service included maritime reconnaissance with Coastal Command and the second line roles of glider-tug, trainer and transport aircraft. The type was also procured by British Overseas Airways Corporation as a civilian freighter aircraft. The aircraft was named after Whitley, a suburb of Coventry, home of one of Armstrong Whitworth’s plants.

The Armstrong Whitworth Whitley was a twin-engined medium bomber, initially being powered by a pair of 795 h.p. Armstrong Siddeley Tiger IX radial engines. More advanced models of the Tiger engine equipped some of the later variants of the Whitley; starting with the Whitley Mk IV variant, the Tigers were replaced by a pair of 1,030 h.p. Rolls-Royce Merlin IV liquid-cooled engines. The adoption of the Merlin engine gave the Whitley a considerable boost in performance.

The early examples had a nose turret and rear turret, both being manually operated and mounting one Vickers machine gun. On the Whitley Mk III this arrangement was substantially revised: a new retractable ventral ‘dustbin’ position was installed mounting twin Browning machine guns and the nose turret was also upgraded to a Nash & Thompson power-operated turret. On the Whitley Mk IV, the tail and ventral turrets were replaced with a Nash & Thompson power-operated turret mounting four Browning machine guns; upon the adoption of this turret arrangement, the Whitley became the most powerfully armed bomber in the world against attacks from the rear

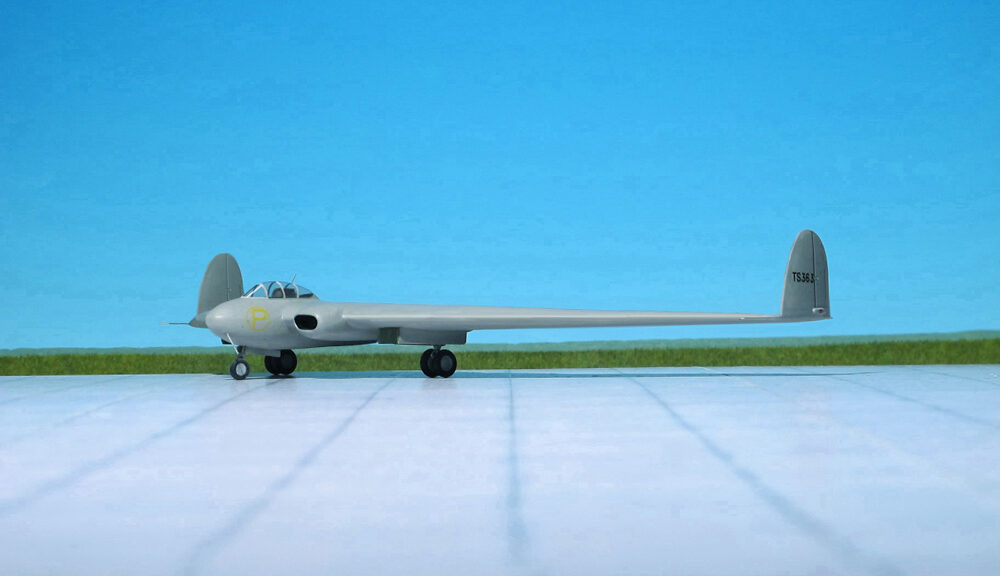

The fuselage comprised three sections, with the main frames being riveted with the skin and the intermediate sections being riveted to the inside flanges of the longitudinal stringers. Extensive use of Alcad sheeting was made. Fuel was carried within a total of three tanks, a pair of 182 gallon tanks contained within the leading edge of each outer wing and one 155 gallon tank in the roof of the fuselage, over the spar centersection; two auxiliary fuel tanks could be installed in the front fuselage bomb bay compartment. The inner leading edges contained the oil tanks, which doubled as radiant oil coolers. To ease production, a deliberate effort was made to reduce component count and standardised parts. The fuselage proved to be robust enough to withstand severe damage.

The Whitley featured a large rectangular-shaped wing; its appearance led to the aircraft receiving the nickname “the flying barn door”. Like the fuselage, the wings were formed from three sections, being built up around a large box spar with the leading and trailing edges being fixed onto the spar at each rib point. The forward surfaces of the wings were composed of flush-riveted, smooth and unstressed metal sheeting; the rear 2/3rds aft of the box spar to the trailing edge, as well as the ailerons and split flaps was fabric covered. The inner structure of the split flaps was composed of duralumin and ran between the ailerons and the fuselage, being set at a 15–20 degree position for taking off and at a 60 degree position during landing. The tailplanes employed a similar construction to that of the wings, the fins being braced to the fuselage using metal struts the elevators and rudders incorporated servo-balancing trim tabs

Designed for service with Coastal Command and carried a sixth crew member, capable of longer-range flights of 2,300 mi compared to the early version’s (1,250 mi) having additional fuel tanks fitted in the bomb bay and fuselage, equipped with Air to Surface Vessel (ASV Mk II) radar for anti-shipping patrols with an additional four ‘stickleback’ dorsal radar masts and other antennae:

Long-range Coastal Command Mk VII variants were among the last Whitleys remaining in front-line service, remaining in service until early 1943. The first U-boat kill attributed to the Whitley Mk VII was the sinking of the German submarine U-751 on 17 July 1942, which was achieved in combination with a Avro Lancaster heavy bomber. Having evaluated the Whitley in 1942, the Fleet Air Arm operated a number of modified ex-RAF Mk VIIs from 1944 to 1946, to train aircrew in Merlin engine management and fuel transfer procedures. Production ended in June 1943 after 1.814 Whitleys being built (Ref.: 24).