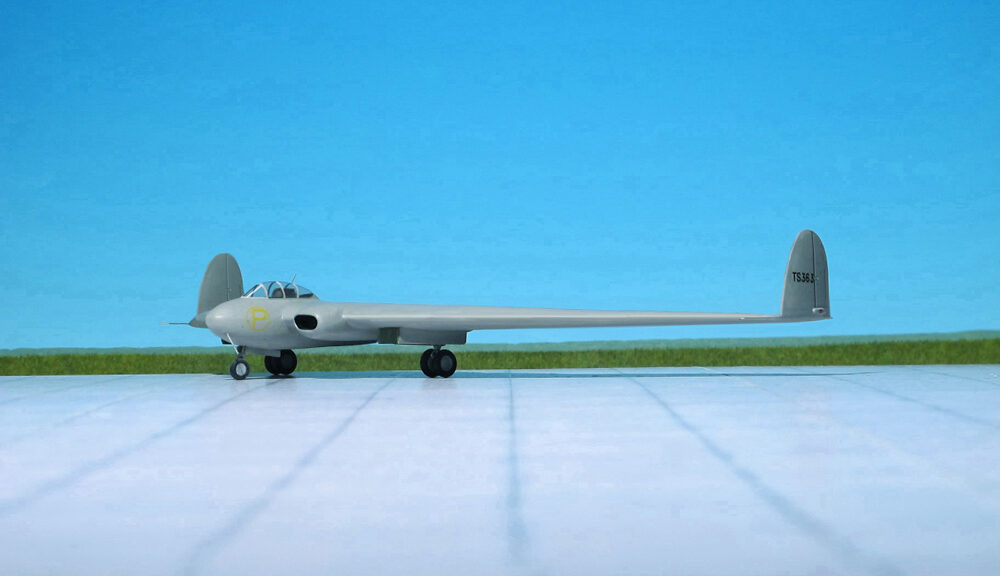

TYPE: Medium bomber, transport aircraft

ACCOMMODATION: Crew of four plus 10 paratroopers

POWER PLANT: Two Bristol Hercules XI radial engine, rated at 1,590 hp each

PERFORMANCE: 265 mph at 10,500 ft

COMMENT: The Armstrong Whitworth A.W.41 Albemarle was a British twin-engine transport aircraft that entered service during the WW II.

The Albemarle was originally designed as a medium bomber that was used for general and special transport duties, paratroop transport and glider towing, including Normandy and the assault on Arnhem during Operation Market Garden.

Air Ministry Specification B.9/38 required a twin-engine medium bomber of wood and metal construction, that could be built by manufacturers outside the aircraft industry and without using light alloys. The Air Ministry was concerned that if there was a war, the restricted supply of materials might affect construction of bombers.

Armstrong Whitworth, Bristol and de Havilland were approached for designs.

Bristol proposed two designs – a conventional 80 ft wingspan capable of 300 mph, and a tricycle design with 70 ft span with a maximum speed of 320 mph. Both designs, known as the Type 155, used two Bristol Hercules engines.

Armstrong Whitworth’s A.W.41 design used a tricycle undercarriage and was built up of sub-sections to ease manufacture by firms without aircraft construction experience. The A.W.41 was designed with Rolls-Royce Merlin engines in mind but with Bristol Hercules as an alternative (“shadow”) engine.

In June 1938, mock-ups of both the A.W.41 and Bristol 155 were examined and new specifications B.17/38 and B.18/38 were drawn up for the respective designs. De Havilland did not submit a design. The specification stipulated 250 mph at 15,000 ft economical cruise while carrying 4,000 lb of bombs. Bristol was already busy with other aircraft production and development and stopped work on the 155.

Changes in policy made the Air Staff reconsider the Albemarle as principally a reconnaissance aircraft capable of carrying out bombing. Among other effects, this meant more fuel to give a 4,000 mi range. Two defensive positions were added; an upper dorsal turret, and a (retractable) ventral turret to enable downward firing.

In October 1938, 200 aircraft were ordered “off the drawing board” (i.e. without producing a prototype first). The aircraft was always expected to be of use as a contingency and to be less than ideal.

The Albemarle was a mid-wing, cantilever monoplane with twin fins and rudders.. The fuselage was built in three sections; the structure being unstressed plywood over a steel tube frame. The forward section used stainless steel tubing to reduce interference with magnetic compasses. It had a Lockheed hydraulically operated, retractable tricycle landing gear, with the main wheels retracting back into the engine nacelles and the nose wheel retracting backwards into the front fuselage.

The two pilots sat side-by-side with the radio operator behind the pilots and the navigator sat in the nose forward of the cockpit. The bomb aimer’s sighting panel was incorporated into the crew hatch in the underside of the nose. In the rear fuselage were glazed panels for a “fire controller” to coordinate the turrets against attackers. The dorsal turret was a Boulton-Paul design with four Browning machine guns. A fairing forward of the turret automatically retracted as the turret rotated to fire forwards. Fuel was in four tanks and additional tanks could be carried in the bomb bay.

A notable design feature of the Albemarle was its undercarriage, which included a retractable nose-wheel (in addition to a semi-concealed “bumper” tail-wheel). It was the first British-built aircraft with this configuration to enter service with the Royal Air Force.

The original bomber design required a crew of six including two gunners; one in a four-gun dorsal turret and one in a twin-gun ventral turret but only the first 32 aircraft, the Mk I Series I, were produced in this configuration, and they were only used operationally as bombers on two occasions. The Albemarle was considered inferior to other aircraft already in service, such as the Vickers Wellington. All subsequent aircraft were built as transports, called either “General Transport” (GT) or “Special Transport” (ST).

When used as a paratroop transport, ten fully armed troops could be carried. The paratroopers were provided with a dropping hatch in the rear fuselage and a large loading door in the fuselage side.

The production run of 600 Albemarles was assembled by A.W. Hawksley Ltd of Gloucester, a subsidiary of the Gloster Aircraft Company formed to build the Albemarle. Gloster was a part of the Hawker Siddeley group which included Armstrong Whitworth. Individual parts and sub-assemblies for the Albemarle were produced by about 1,000 subcontractors

The first Albemarle first flew on March 1940 at Hamble Aerodrome, where it was assembled by Air Service Training and was the first of two prototypes built by Armstrong Whitworth. To improve take-off, a wider span 77 ft wing was fitted after the eighth aircraft. Plans for using it as a bomber were dropped due to delays in reaching service, it was not an improvement over current medium bombers (such as the Vickers Wellington) and it had obvious shortcomings compared to the four-engine heavy bombers about to enter service but it was considered suitable for general reconnaissance.

From mid-1943, RAF Albemarle’s took part in many British airborne operations, such as invasion of Sicily (1943), D-Day (1944), Operation Tonga (1944), Operation Mallard (1944) and Operation Market Garden (1944).The gliders that were to towed included Airspeed Horsa’s, General Aircraft Hamilcar’s, and Waco Hadrian’s.

Of the 602 Albemarles delivered, 17 were lost on operations and 81 lost in accidents (Ref. 24).