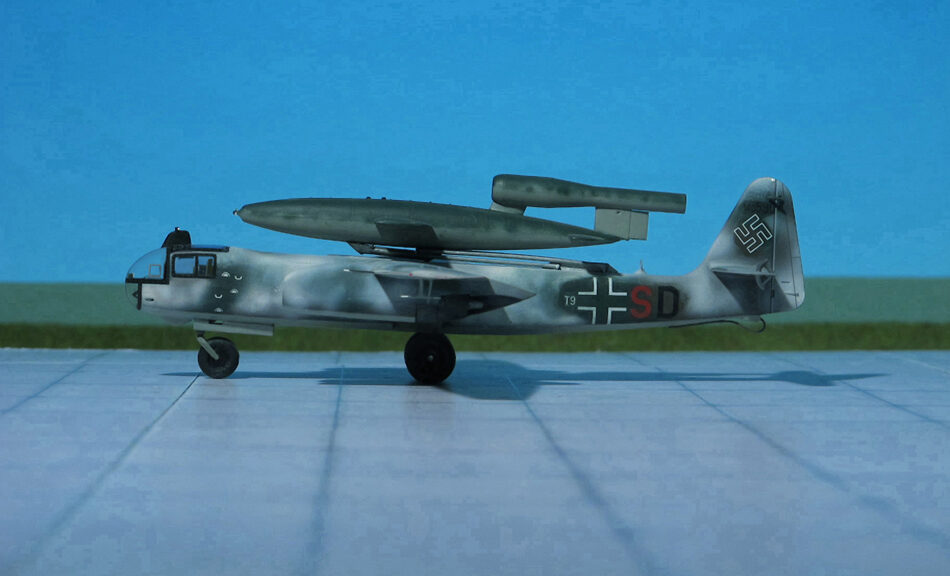

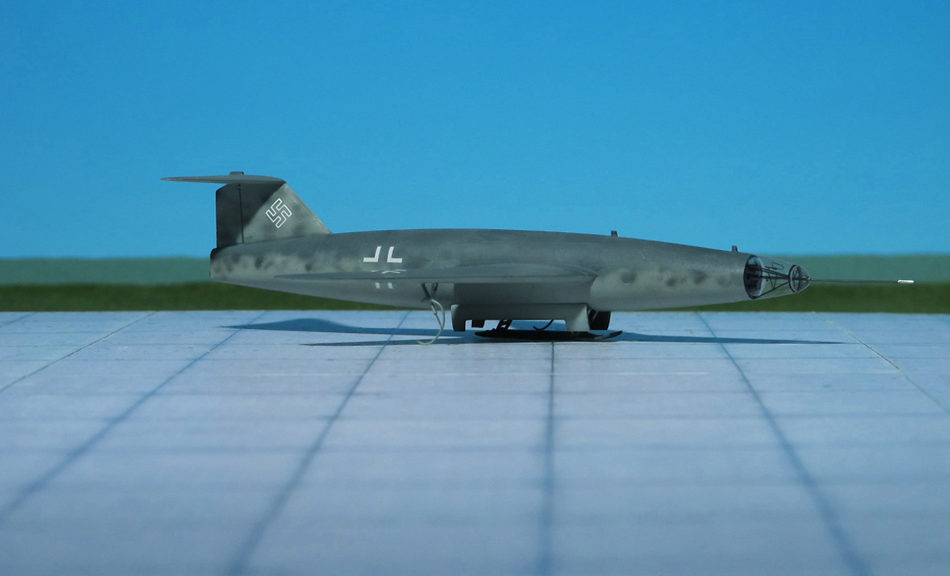

TYPE: Long-range strategic bomber, maritime reconnaissance aircraft

ACCOMMODATION: Crew of eight

POWER PLANT: Four BMW 801 G radial engines with turbochargers and GM-1 boost system., rated at 1,750 hp each for take-off

PERFORMANCE: 351 mph at 27,230 ft with GM-1 operating

COMMENT: The Messerschmitt Me 264 was a long-range strategic bomber developed during WW II for the German Luftwaffe as its main strategic bomber. The design was later selected as Messerschmitt’s competitor in the Reichsluftfahrtministerium’s (RLM, German Air Ministry) Americabomber programme, for a strategic bomber capable of attacking New York City from bases in France or the Azores.

Three prototypes were built but production was abandoned to allow Messerschmitt to concentrate on fighter production (Messerschmitt Me 262) and the Junkers Ju 390 was selected in its place. Nevertheless, development oft he Me 264 continued as a maritime reconnaissance aircraft instead.

The origin of the Me 264 design came from Messerschmitt’s long-range reconnaissance aircraft project, the P.1061 of the late 1930‘s. A variant on the P.1061 was the P.1062 of which three prototypes were built, with only „two engines” to the P.1061’s four, but they were, in fact, the more powerful Daimler Benz DB 606 “power systems”, each comprising a pair of DB 601 inverted V-12 engines. These engines were successfully used in the long-range Messerschmitt Me261 itself originating as the Messerschmitt P.1064 design of 1937. Also, the DB 606 engine powered Heinkel He 177A heavy bomber. In early 1941, six P.1061 prototypes were ordered from Messerschmitt, under the designation Me 264. This was later reduced to three prototypes.

The Me 264 was an all-metal, high-wing, four-engine heavy bomber of classic construction. The fuselage was round in cross-section and had a cabin in a glazed nose, comprising a “stepless cockpit” with no separate windscreen section for the pilots, which was common for most later German bomber designs. A strikingly similar design was used for the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, of slightly earlier origin. The wing had a slightly swept leading edge and a straight trailing edge. The empennage had double tail fins. The undercarriage was a retractable tricycle gear with large-diameter wheels on the wing-mounted main gear.Overall, it carried very little armour and few guns as a means of increasing fuel capacity and range.

The first prototype, the Messerschmitt Me 264 V1, bearing the Stammkennzeichen (factory code) RE+EN, was flown on 23 December 1942. It was powered at first by four Junkers Jumo 211J inline engines of 1,340 hp each. In late 1943, these were changed to the BMW 801G radials which delivered 1,750 hp. Trials showed numerous minor faults and handling was found to be difficult. One of the drawbacks was the very high wing loading of the Me 264 in fully loaded conditions. The relatively high wing loading caused poor climb performance, loss of manoeuvrability, stability and high take-off and landing speeds. The first prototype was not fitted with weapons or armour. On 18 July 1944, the Me 264 V1, which had entered service with Transportstaffel 5 (Transport Wing 5) ,was damaged during an Allied bombing raid and was not repaired.

The second prototype Me 264 V2, Stammkennzeichen (factory code) RE+EO, was to be powered by for BMW 801G radial engines with turbochargers and GM-1 injection. The wing-span was extended and 1.000 kg of armor added around the more vital parts of the aircraft. For increased range six additional auxillary fuel tanks were mounted under the wings. Due to compensade overweight two droppable auxiliary wheels were attached to the main landing gear.

The third prototype was unfinished and destroyed during the same raid. In October 1943. So officially, further development of the Me 264 was stopped to concentrate on the production of the Messerschmitt Me 262 turbojet-fighter.

Nevertheless, Messerschmitt was convinced in increased requirements of a multi-engine long-range bomber/reconnaissance aircraft. So the design team still worked on a six-engine version of the Me 264, the Me 264/6m (or alternatively Me 364). But the collaps of the „Third Reich“ ended all activities (Ref.: 24).