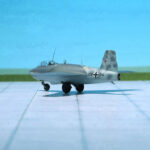

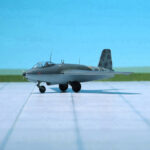

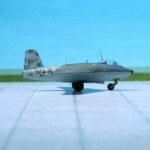

TYPE: Fighter interceptor

ACCOMMODATION: Pilot only

POWER PLANT: One Walter HWK 109-509C-3 dual-chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine,main chamber rated up to 2,000 kp thrust, auxiliary chamber 400 kp thrust

PERFORMANCE: 590 mph

COMMENT: The Messerschmitt Me 263 „Scholle“ (Plaice) was a rocket-powered fighter aircraft developed from the Messerschmitt Me 163 „Komet“ (Comet) towards the end of WW II. Three prototypes were built but never flown under their own power as the rapidly deteriorating military situation in Germany prevented the completion of the test program.

Although the Messerschmitt Me 163 had very short endurance, it had originally been even shorter. In the original design, the engine had only one throttle setting, “full on”, and burned through its fuel in a few minutes. Not only did this further limit endurance, in flight testing, pilots found the aircraft quickly exhibited compressibility effects as soon as they levelled off from the climb and speeds picked up. This led the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) to demand the addition of a throttle, leading to lengthy delays and a dramatic decrease in fuel economy when throttled.

This problem was addressed in the slightly updated Messerschmitt Me 163C. This featured the same Walter HWK 109-509B or C dual chamber rocket engine already trialled on the Me 163B V6 and V18 prototypes; the main upper chamber („Hauptkammer“) was tuned for high thrust while the lower „Marschofen“ auxiliary combustion chamber was designed for a much lower thrust output (about 400 kgf maximum) for economic cruise. In operation, throttling was accomplished by starting or stopping the main engine, which was about four times as powerful as the smaller one. This change greatly simplified the engine, while also retaining much higher efficiency during cruise. Along with slightly increased fuel tankage, the powered endurance rose to about 12 minutes, a 50% improvement. As the aircraft spent only a short time climbing, this meant the time at combat altitude would be more than doubled.

Throughout development the RLM proved unhappy with the progress on the Me 263 project, and eventually decided to transfer development to Heinrich Hertel at Junkers company. Alexander Lippisch remained at Messerschmitt and retained the support of Waldemar Voigt, continuing development of the Me 163C.

At Junkers, the basic plan of the Me 163C was followed to produce an even larger design, the Junkers Ju 248. It retained the new pressurized cockpit and bubble canopy of the Me 163C, with even more fuel tankage, and adding a new retractable landing gear design. On September 1944 a wooden mock-up was shown to officials. The production version was intended to be powered by the more powerful BMW 109-708 rocket engine in place of the Walter power plant.

Prior to the actual building of the Ju 248, two Me 163Bs, prototype V13 and V18, were slated to be rebuilt. V13 had deteriorated due to weather exposure, so only V18 was rebuilt, but had been flown by test pilot Heini Dittmar at a record-setting 702 mph velocity on July , 1944 and suffered near-total destruction of its rudder surface as a result of high-speed induced compressibility. It is this aircraft that is often identified as the Me 163D, but this aircraft was built after the Ju 248 project had started.

Hertel had hoped to install Lorin ramjet engines, but this technology was still far ahead of its time. As a stopgap measure, they decided to build the aircraft with a „Sondergeräte“ (special equipment) in the form of a „Zusatztreibstoffbehälter“ (auxiliary fuel tank): two 160 l external T-Stoff oxidizer tanks were to be installed under the wings. This would lead to a 10% speed decrease but no negative flight characteristics. Although Junkers claimed the Ju 248 used a standard Me 163B wing, they decided to modify the wing to hold more C-Stoff fuel. This modification was carried out by the Puklitsch firm.

In November 1944, the aircraft was again redesignated as the Messerschmitt Me 263 to show its connection with the Me 163. The two projects also got names – the Ju 248 „Flunder“ (Flounder)) and the Me 263 „Scholle“ (Plaice)). In early 1945, Junkers proposed its own project, the EF 127 „Walli“ rocket fighter, as a competitor to the Me 163C and Me 263.

The first unpowered flight of the Messerschmitt Me 263 V1 was in February 1945. Several more unpowered flights took place that month. The biggest problem had to do with the center of gravity which was restored with the addition of counterweights. Eventually, the production aircraft would have repositioned the engine or the landing gear installation to solve this problem. The landing gear was still non-retractable. The results of those first flights were pricipally satisfying.

Test flights were later stopped because of fuel shortages for the Messerschmitt Bf 110 towplanes. As the Me 263 was not a part of the „Jägernotprogramm“ (Emergency Fighter Programm), it was difficult to get the resources it needed. For the time being the plane was not expected to enter production but further development was allowed. The V2 and V3 were not yet ready. The V2 was to get the retractable landing gear and the V3 would have the armament built in. The next month both the V1 and the V2 had the two-chambered HWK 109-509C installed, correcting the center-of-gravity problems. They flew only as gliders.

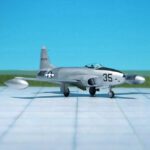

In April, American troops occupied the Messerschmitt plant and captured the three prototypes and the mock-up. The V2 was destroyed but another prototype ended up in the US. The rest was handed over to the Russians, who then created their own Mikoyan.Gurewitsch I-270 interceptor (Ref.: 24).