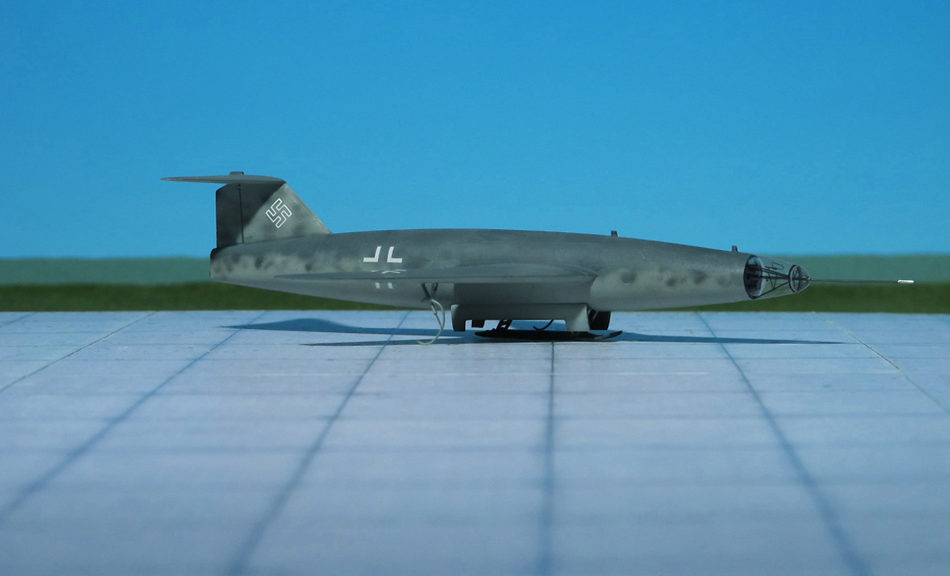

TYPE: High-speed, high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft

ACCOMMODATION: Pilot only, in prone position

POWER PLANT: One Walter HWK 109-509 liquid-fuel rocket, rated at 3,400 kp thrust

PERFORMANCE: 560 mph (verified), 1,723 mph (estimated)

COMMENT: The DFS 346 was a German rocket-powered swept-wing aircraft subsequently completed and flown in the Soviet Union after WW II. It was designed by Felix Kracht at the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug (DFS, “German Research Institute for Sailplanes”). The prototype was still unfinished by the end of the war and was taken to the Soviet Union where it was rebuilt, tested and flown.

The DFS-346 was a midwing design of all-metal construction. The front fuselage of the DFS 346 was a body of rotation based on the NACA-Profile 0012-0,66-50. The middle part was approximately cylindrical and narrowed to the cut off to accommodate vertically arrayed nozzles in back. Probably for volume and weight reasons the DFS-346 was equipped with landing skids, both in the original German design and in the later Soviet prototypes; this caused trouble several times.

The wings had a 45° swept NACA 0012-0,55-1,25 profile of 12% thickness. The continuously varying profile shape caused a stall in certain flight conditions, which caused complete loss of control. This was later corrected by use of fences on the top of the wings.

The DFS 346 was a parallel project to the DFS 228 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, designed under the direction of Felix Kracht and his team at DFS. While the DFS 228 was essentially of conventional sailplane design, the DFS 346 had highly-swept wings and a highly streamlined fuselage that its designers hoped would enable it to break the sound barrier.

Like its stablemate, it also featured a self-contained escape module for the pilot, a feature originally designed for the DFS 54 prior to the war. The pilot was to fly the machine from a prone position, a feature decided from experience with the first DFS 228 prototype. This was mainly because of the smaller cross-sectional area and easier sealing of the pressurized cabin, but it was also known to help with g-force handling.

The DFS 346 design was intended to be air-launched from the back of a large mother ship aircraft for air launch, the carrier aircraft being the Dornier Do 217K as with the DFS 228. After launch, the pilot would fire the Walter HWK 109-509B/C twin-chamber engine to accelerate to a proposed speed of Mach 2.6 and altitude of 100,000 ft. This engine had two chambers — the main combustion chamber as used on the earlier HWK 509A motor; but capable of just over two short 2,000 kp of thrust at full power, and the lower-thrust “Marschofen”, (Cruise chamber = throttleable chamber of either 300 kp (B-version) or 400 kp (C-version) top thrust levels mounted beneath the main chamber. After reaching altitude, the speed could be maintained by short bursts of the lower “Marschofen” (cruise chamber).

In an operational use the plane would then glide over England for a photo-reconnaissance run, descending as it flew but still at a high speed. After the run was complete the engine would be briefly turned on again, to raise the altitude for a long low-speed glide back to a base in Germany or northern France.

Since the aircraft was to be of all-metal construction, the DFS lacked the facilities to build it and construction of the prototype was assigned to Siebel Werke located in Halle, where the first wind tunnel models and partially built prototype were captured by the advancing Red Army.

On 22 October 1946, the Soviet OKB-2 (Design Bureau 2), under the direction of Hans Rössing and Alexandr Bereznyak, was tasked with continuing its development. The captured DFS 346, now simply called “Samolyot 346” (“Samolyot” = Aircraft) to distance it from its German origins, was completed and tested in TsAGI wind tunnel T-101. Tests revealed some aerodynamic deficiencies which would result in unrecoverable stalls at certain angles of attack. This phenomenon involved a loss of longitudinal stability of the airframe. After the wind tunnel tests, two wing fences were installed on a more advanced, longer version of the DFS-346, the purpose of fences was to interrupt the spanwise movement of airflow that would otherwise bring the boundary-layer breakdown and transition from attached to stalled airflow with loss of lift and increase of drag.

This solution was used on the majority of the Soviet planes with sweptback wings of the 1950s and 1960s. In the meantime, the escape capsule system was tested from a North American B-25J “Mitchell” piston engine medium bomber and proved promising. Despite results from studies showing that the plane would not have been able to pass even Mach 1, it was ordered to proceed with construction and further testing.

In 1947, an entirely new 346 prototype was constructed, incorporating refinements suggested by the tests. This was designated “346-P” (“P” for planer = “glider”). No provision was made for a power plant, but ballast was added to simulate the weight of an engine and fuel. This was carried to altitude by a Boeing B-29 “Superfortress” captured in Vladivostok and successfully flown by Wolfgang Ziese in a series of tests. This led to the construction of three more prototypes, intended to lead to powered flight of the type.

Newly built “346-1“ incorporated minor aerodynamic refinements over the 346-P, and was first flown by Ziese on September 30, 1948, with dummy engines installed. The glider was released at an altitude of 9700 m, and the pilot realized that he hardly could maintain control of the aircraft. Consequently, while attempting to land, he descended too fast (his speed was later estimated at 310 km/h). After first touching the ground he bounced up to a height of 3–4 m and flew 700–800 m. At the second descent, the landing ski collapsed and the fuselage hit the ground hard.

The pilot seat structure and safety belt proved to be very unreliable, because at the end of a rough braking course Ziese was thrown forward and struck the canopy with his head, losing consciousness. Luckily, he wasn’t seriously injured, and after treatment in hospital he was able to return to flying. Accident investigation research team came to the conclusion that the crash was a result of pilot error, who failed to fully release the landing skid. This accident showed that the aircraft handling was still very unpredictable, as a result, all rocket-powered flights were postponed until pilots were able to effectively control the aircraft in unpowered descent, requiring further glide flights.

The damaged 346-1 was later repaired and modified to 346-2 version. It was successfully flown by test pilot P. Kazmin in 1950-1951 winter, but nonetheless these flights also ended “on fuselage”. Furthermore, after the last flight of these series, the airframe again required major repairs. On 10 May 1951, Ziese returned to the program, flying final unpowered test flights with the 346-2, and from 6 June, unpowered tests of the 346-3 without accidents.

By the mid-1951 346-3 was completed, and Ziese flew it under power for the first time on 13 August 1951, using only one of the engines. Continuing concerns about the aircraft’s stability at high speeds had led to a speed limit of Mach 0.9 being placed during test flights. Ziese flew it again on 2 September and 14 September. On this last flight, however, things went drastically wrong. Separating from the carrier plane at 9,300 meters (30,500 ft) above Lukovici airfield, the pilot fired the engine and accelerated to a speed of 900 km/h (560 mph). The rocket engine worked as expected, and 346-3, quickly accelerating, started ascending and soon had flown in very close proximity of its carrier aircraft. Ziese then reported that the plane was not responding to the controls, and was losing altitude. Ground control commanded him to bail out. He used the escape capsule to leave the stricken aircraft at 6,500 meters (21,000 ft) and landed safely by parachute. With the loss of this aircraft, the 346 program was abandoned (Ref.:24).